this blog has now finished

July 14, 2010Auto-Building Dwelling thinking

June 30, 2010Having developed an interest lately in all things architecture related, I came across a website called ‘Singularity University’ which is a non-profit organization funded by big names such as Google and Autodesk, whose stated mission is “to assemble, educate and inspire a cadre of leaders who strive to understand and facilitate the development of exponentially advancing technologies in order to address humanity’s grand challenges.” ‘Technological singularity’ an idea of rapid and inevitable technology progresses. Rapid rates of technological capacity could introduce new ‘intelligent’ technologies, leading to an ‘intelligence explosion’ where sudden, exponential growth generates paradigmatic and qualitative changes in the the human condition. Some have called this transhumanism. As this organization clearly sees technology as the answer to all our problems, they featured a presentation from a company called Acasa, which is developing machines for building houses with the minimum of human labour and time using a process called ‘contour crafting’, the 3D printing of housing. The entire process of house building the envelope and skeleton of a house can be automated, with the possibility of other automatic systems that can furnish, construct and install electrical and plumbing networks throughout.

Here’s a a computer generated simulation of the process of construction:

Obviously, the idea is being sold on the basis of a humanitarian imperative, as indicated through the initial video I watched on the Singularity University site. Natural disasters and urban sprawl means that over a billion people live in dwellings with little or no resources such as running water and electricity. Most of these are not built to a sufficient quality to resist storms, earthquakes and other such dangers that could be detrimental to safety. By building houses in one day with minimal labour and waste, many more people can be house before and after a disaster has occurred.

However, I’m sure that the incentive for developing such building technologies go beyond their altruistic applications towards more profitable applications. For instance, even though the construction industry is known for it’s employment of immigrant labour to keep costs to a minimum, exploitative practises are rife (see this article HERE for a case study of Dubai’s skyscrapers built with the sweat of cheap labourers). If contour crafting and it’s other sister technologies develop to the stage of industry wide take up, it will mean a massive de-skilling of labour from the activities of construction, but a re-skilling of labour away from the craft of building towards the maintenance of the building machines and the maintenance of the reserves needed for assemblage. However, the ratio of re-skilled to de-skilled will be dramatically unbalanced, where the number of re-skilled has shrunk and where a division of labour can be applied at the level of re-skilling to eliminate the need for over-skilled labourers. The prospect of automation reaching the construction industry is both exciting and bleak, yet this relation to dwelling, building and labour needs to thought through.

I was going to write some more but must get some sleep. I’ll be away in London in the next few days for Marxism 2010, so I’ll just say I intend to write a bit about automation, de-skilling and ‘dwelling’ (gotta throw in a bit of Heidegger here and there) when I get back next week.

Meritocracy and inheritance

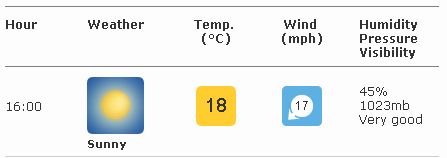

June 29, 2010

The above picture is a scan from the news magazine The Week (issue 772). I thought the juxtaposition was quite upsetting, so I decided it needed to be shared. Here are two excellent examples of the inequalities inherent in our systems of wealth distribution: one story shows the obscene wealth and decadence of the American rich and the other shows the poverty and suffering of one of the world poorest nations. This has to stop.

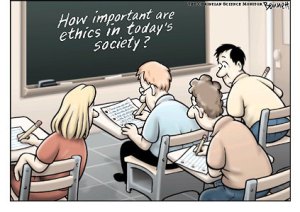

I recently finished an excellent little book from Zero books called The Meaning of David Cameron by Richard Seymour. A large part of the text was taken up by discussions of the term ‘meritocracy’ and its appropriation by the left and right. It is used as a progressive term to signify that “one should rise or fall by one’s own merits” in a society of equal opportunity. Thus any individual’s own effort and natural genius morally justifies their own financial successes: Everyone is equal in opportunity but unequal in character. Seymour goes on to discuss the research of Stephen Aldridge of the Cabinet Office’s Performance and Innovation Unit, who presented his work to the Blairite ‘third way’ sociologists, such as Anthony Giddens.

He said that to have a ‘strong’ version of meritocracy, it would be necessary to raise taxes on income and investments, and abolish inheritance. For social mobility to realistically take place, it had to be possible to move down as well as up the scale, and thus it would be necessary to “reduce barriers to downward social mobility for dull middle class children”. The Government distanced itself from these findings – this was not the meritocracy that had in mind. (p.55)

To follow the logic of meritocracy one would need to increment a dissolution of inheritance, otherwise the premise of ‘equality’ in a meritocracy is false. The hypocrisy of meritocracy is clear for all to see, and I agree with Seymour that it is a “collective insult on humankind”. If a supposedly socialist party such as Labour is unwilling to introduce such measures and the conservatives are about as likely to drop inheritance as throw eggs at the Queen, then why is dropping inheritance a faux pas, even when it coincides with the logic of our contemporary [fascistic] form of neoliberalism?

In The Communist Manifesto Marx lists the “abolition of all right of inheritance” third in a list of 10 procedures to be enacted once state power has been claimed by the dictatorship of the proletariat and the expropriators are expropriated. Inheritance is very important as a consequence of the destruction of capitalism, but as Marx noted in The Right of Inheritance eliminating inheritance tout court would not rid society of the structures of private property and therefore may not be a progressive move towards communism at all: the relations of society are still essentially the same. “Inheritance does not create that power of transferring the produce of one man’s labor into another man’s pocket — it only relates to the change in individuals who yield that power” (Marx). To use the bourgeois powers to eliminate inheritance would seemingly be impossible, given that one major point of inheritance is for one’s children to be protected from hardships after the death of a dependent. The incentive for wealth accumulation and the provision of family assets such as homes and savings would be limited if inheritance was abolished. Although it would ultimately take one avenue of social mobility away from the rich, the basic capitalist desire would still be based on individual self-interest, personal wealth accumulation and appropriation of others labour as a means of financial success.

To proclaim the abolition of the right of inheritance as the starting point of the social revolution would only tend to lead the working class away from the true point of attack against present society. It would be as absurd a thing as to abolish the laws of contract between buyer and seller, while continuing to present state of exchange of commodities. (Marx)

Even if inheritance was abolished, it would only encourage capital flight and devious loopholes to ensure assets end up in the ‘right’ pockets. To abolish inheritance is not a solution to redistributing wealth, but it shows how the logic of accumulation is bound to the family as a centre for protection and privilege. This helps to maintain structures of class inequality and social immobility within a meritocracy.

However, even though inheritance is an effect not the cause of inequality, if there was a referendum on the issue, I know how I would vote, although, as “Professional white owner-occupiers are most likely to receive an inheritance” I’m not sure this lot would agree:

[Audio lecture summary] John D. Caputo: Agamben and the flesh

June 16, 2010 These are my notes from an extremely informative lecture by Caputo on Agamben. He covers a lot of ground, including the books The Open and The Coming Community, while also referencing Heidegger, Deleuze, Merleau-Ponty, Sartre and a few random Scholastics, as part of a lecture series on ‘philosophies of the flesh’. This can be found HERE all Caputo’s lectures can be found on his website, which is HERE

These are my notes from an extremely informative lecture by Caputo on Agamben. He covers a lot of ground, including the books The Open and The Coming Community, while also referencing Heidegger, Deleuze, Merleau-Ponty, Sartre and a few random Scholastics, as part of a lecture series on ‘philosophies of the flesh’. This can be found HERE all Caputo’s lectures can be found on his website, which is HERE

Agamben sketches out a history of metaphysics according to the anthropological machine. This is the history of humanism defined as politics. Heidegger is seen as the last thinker of humanism (as Dasein is the possessor of superior essence) yet is also the great renouncer of humanism: as the ‘human’ doesn’t reach the real essence of humanity which is separated from animals by an abyss. Agamben’s notion of ‘the open’ is that which is a reconciliation of the human with its animality via an ‘attitude’ that opens the condition of salvation. This messianic moment of salvation is the post-historical end of the anthropological machine that produces exclusively human history.

[Quick quote] Heidegger and Fink: Heraclitus Seminar

June 16, 2010Now come, fire!: The sun is blasting through onto my desk today and it’s reminded me of old Heraclitus. Here’s a quick quote from Fink in regards to the Heraclitian notion of Helios:

The times of the day and seasons apparently stand in connection with fire, a fire that does not, like lightening, suddenly tear open and place everything in the stamp of the outline, but that holds out like the heavenly fire, and in the duration, travels through the hours of the day and the times of the season… The heavenly fire brings forth growth. It nourishes growth and maintain it. The light-fire of Ηλιοζ [helios : the sun] tears open – different from lightning – continually; it opens the brightness of day in which it allows growth and allows time to each thing. This sun-fire, the heaven – illuminating power of Ηλιοζ, does not tarry fixed at one single place, but travels along the vault of heaven; and in this passage on the vault of heaven the sun-fire is light – and life-appropriating and time measuring. The metric of the sun’s course mentioned here lies before every calculative metric made by humans. We must think radiant Zeus together with Ηλιοζ as the power of the day which illuminates the entity of τα παντα [ta panta: the many].

(from Heidegger and Fink’s seminar on Heraclitus, p.37 and 39)

[Notes] Guy Debord: Society of the Spectacle

June 16, 2010Before beginning on a summary of the book, these words from Simon Critichely’s Ethics, Politics, Subjectivity are worth a look:

HERE is a link to the film of Society of the Spectacle, fully available on youtube. And HERE’s a link to the writings of all Situationist International thinkers available, in full, on-line.

[Quick article summary] Rocco Gangle: Laruelle for Levinas

June 15, 2010 This is a very quick summary of Rocco’s article Laruelle for Levinas. He uses Plotinus to frame the problem of the relation of the One to enjoyment and sensibility, in regards to Levinas’ move from the ontological (in Totality and Infinity) to the ethical (in Otherwise than Being). Once he has expounded exactly where Levinas makes his crucial Decision in regards to the Real, Gangle reports that even though Levinas never identifies them, the ‘saying’ opens the possibility of torture, persecution and killing,just as much as an ethical response. Gangle uses non-philosophy to remedy this paradox. It’s an excellent article and neatly explains, through demonstration, exactly how non-philosophy works.

This is a very quick summary of Rocco’s article Laruelle for Levinas. He uses Plotinus to frame the problem of the relation of the One to enjoyment and sensibility, in regards to Levinas’ move from the ontological (in Totality and Infinity) to the ethical (in Otherwise than Being). Once he has expounded exactly where Levinas makes his crucial Decision in regards to the Real, Gangle reports that even though Levinas never identifies them, the ‘saying’ opens the possibility of torture, persecution and killing,just as much as an ethical response. Gangle uses non-philosophy to remedy this paradox. It’s an excellent article and neatly explains, through demonstration, exactly how non-philosophy works.

So, to summarize all too quickly: Non-philosophy de-authorizes the Decision that correlates Levinas’ concepts from reciprocal determination of the Real, to concepts taken in their radical contingency. What was taken by Levinas as the condition and the conditioned (of the saying and the said) for ethics as first philosophy is without guarantee: ethics cannot be correlated to a principle governing all material reality (there can be no ethics-in-the-first-instance, as the Real is not ethical – the real is undetermined). Levinas via Laruellian dualysis can be seen to speak as a Stranger not as a philosopher, his concepts given over to the force (of) thought of his genuine address as ‘human disposition’ (his ‘postural flux’), the ‘material vulnerability’ of his “here I am”, freed from the ontological trap between the saying and the said.

In light of Laruelle’s Principles of a Generic ethics essay, Gangle lets causality of Levinas’ philosophy be disentangled from its ends and observed in the immanence of a ‘quarterial’ subject of means. This ‘quarterial’ subject stands not before the face of the Other but the face of the One, where ‘responsibility’ is not determined-in-the-first-instance but in the contingency of-the-last.

I hope to post a summary and explanation of Principles of a Generic Ethics as soon as I’m happy with it (I’ve finally got my head around some of the more abstract things in the article concerning circles, so I should be finished soon). I would like to compare his notion of means to that of Agamben’s ‘means without ends’ at some point, but Agamben I find is deceptively difficult, so I may need to re-read a few things before I make an attempt at that).

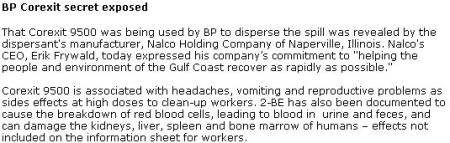

[Website link] World Socialist Website: BP, oil and ‘Corexit’

June 15, 2010![]() For indepth and quite devastating coverage of the BP induced crisis in the Gulf, I suggest looking at the World Socialist Website’s many great articles with a heavily leftist, but well researched and articulated, bent HERE.

For indepth and quite devastating coverage of the BP induced crisis in the Gulf, I suggest looking at the World Socialist Website’s many great articles with a heavily leftist, but well researched and articulated, bent HERE.

This section below is from a WSWS article found HERE

Bea told the WSWS that a contact had provided him with a toxicity statement for Corexit, the dispersant BP is using—so far about 500,000 gallons have been dumped on the surface and near the seabed, and about 800,000 more gallons are on order. “It clearly says, if you breathe too much of it or if you ingest too much of it, if you let too much sit on your skin, it’ll kill you,” Bea said. “And of course I’m sitting here thinking if I’m a fish, I don’t know that.”

A Thursday report in the New York Times, “Less Toxic Dispersants Lose Out in BP Oil Spill Cleanup,” reveals that Corexit is one of the most highly toxic dispersants on the market, and one of the least effective.

“Of 18 dispersants whose use EPA has approved, 12 were found to be more effective on southern Louisiana crude than Corexit, EPA data show,” according to Paul Quinlan of the Times’ Greenwire blog. “Two of the 12 were found to be 100 percent effective on Gulf of Mexico crude, while the two Corexit products rated 56 percent and 63 percent effective, respectively. The toxicity of the 12 was shown to be either comparable to the Corexit line or, in some cases, 10 or 20 times less, according to EPA.”

(the above quote is from HERE)

So why is it being used? Once again, the most immediate profit concerns predominate. Corexit is produced by Nalco Co., a firm headed up by executives from both BP and industry leader Exxon. “It’s a chemical that the oil industry makes to sell to itself, basically,” said Richard Charter of Defenders of Wildlife.

[Quick pic]

June 13, 2010Today I was reading this passage from The Monstrosity of Christ…

and at that moment, I looked up from my window seat at my local coffee shop and what did I see directly in front of me in the road?. . .

I’m sure people have been converted for less. . .

[notes] Zizek and Milbank: The Monstrosity of Christ (part 1)

June 13, 2010Atheism has never been funnier than from the mouth of Zizek. Anyone can blaspheme about God and rely on absurdest mockery, but only Zizek can take the priest by the cross and tell them with all sincerity that “only atheists can truly believe”. For in the mind of Zizek, it is atheism that exemplifies the properly dialectical logic of the Event of Christ as to truly understand Christ one has to take the death of God through to its traumatic conclusion. This is a series of notes and summaries of some of the important arguments from the book.

The introductory piece by the editor Creston Davis sets the scene between the two theoretical juggernauts that are Slovoj Zizek and John Milbank. It is written in a theory laden and condensed manner that spell out the political implications and emancipatory stakes in both positions (as I exemplified in this quick quote post HERE). The point of the book is to overcome the myopia of contemporary public debates played out in the best sellers lists between figures such as Dawkins and McGrath by exposing the limitation of their rational dismissal of the other. Dawkins relies on belittling metaphors about spaghetti monsters to expose the absurd logic of theism while leaving the presumptions about his own use of reason and logic intact.

What Zizek and Milbank agree on is that the terms of debate need to be reassessed not rehashed and sold as lower-middle class coffee table reading or quotable toilet book material (such must be the destination for Hitchen’s rhetorical The Quotable Atheist). The point of tension for Zizek and Milbank is Hegel: the true thinker of the dialectic and therefore the thinker of the contradiction of atheism and fideism. This takes my mind back to my reading of After Finitude. Here’s a section from my notes that nicely summarizes the state of the situation:

Even after successfully critiquing meta-physico religiosity, this does not disprove God but only a type of God which appeals to natural reason to declare the superiority of its own beliefs. To remove proof of the ‘supreme’ supported by reason reverses the process of the destruction of polytheistic religion suffered at the hands of monotheistic religious reason (p.45). What does this produce? Fundamentalist fideism: a defence of religiosity in general which promotes the superiority of piety over thought, thus removing reason from any ground to a belief in God or gods. The result is a religionizing of reason: beliefs are legitimate as nothing but beliefs, not as reasonable beliefs (p.47). Philosophical works such as by Levinas pursue a sceptico-fideist closure of metaphysics dominated by the ‘wholly-other’ (p.48). Fideism is merely another name for strong correlationism. The correlationist cogito can thus be non-representational and institutes a species solipsism (rather than individual solipsism – Heidegger’s being-in-the-world could be a species solipsist claim).

For me, this was the best stuff from After Finitude, as it explained the resurgence of theology in the modern world impeccably. Obviously, Zizek is looking to reassert the Enlightenment logic of Hegel’s dialectic to overcome the end of the principle of sufficient reason where God is the guarantor of necessary and meaning existence. Milbank, however, is looking to reassert the primacy of theology through a positive ontology that answers Meillassoux’s concerns over the status of reason itself. Both Zizek and Milbank are determined to use Hegel as the linchpin of their respective positions, but having only read Zizek’s part so far I cannot comment on just how Milbank appropriates the Hegelian dialectic.

For a good overview of how Zizek understands the subject to come from being torn asunder between a barred nature and culture, see my post on Adrian Johnston explaining the ambiguities of Zizek’s reading of the Lacanian ‘death drive’ HERE.

Zizek nicely summarizes his position again and again, here is an example:

It is easy to follow from this just how Zizek’s Communist politics dovetails nicely into this deduction: Communism is true birth of the holy ghost as love and solidarity between subjects that have overcome their reliance on transcendence and embraced the true meaning of Jesus’ message when he says “Lay not up for thyself treasures, whereby thou stealest from thy neighbour and markest him to starve: for when hast thy goods safeguarded by the law of man, thou provokest thy neighbour to sin against the law” (p.70). Zizek interprets this to mean ‘property is theft’, to which Marx’s call for the abolition of private property is an echo of Jesus’ sermon!

Zizek goes on to use Meister Eckhart’s notion of the Godhead, the void-One beyond Word that Zizek will characterize as ‘un-God’. The un-God does not have positively existence (1) as it is nothing (0). Creation thus comes from nothing:

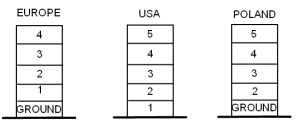

This lead into the final stretches of his chapter which frame his Hegelian dialectics within the atheistic confines of Badiou’s mathematical ontology: the background of multiple multiplicities of the void (as zero) which can never have a final substrata (‘the One is not’). This is materialist without the assertion of a foundational material density, but a materialism taken to its limit assumes only void. To demonstrate how the ground (0) is also the place of figuration (1) I’ll illustrate Zizek’s example using international floor numbering principles for buildings:

Poland has the correct solution, Zizek assures us, as the ground floor is that which is “always-already given, and as such, cannot be counted”, but “the moment one starts to count the floors the ground floor itself must be counted as one”. The ground as nothing comes before any count, and anything that is counted has, ultimately, nothing as its ground. Zizek’s negative ontology converges with Badiou’s on this point, but separtes over the understanding of human animality.

Badiou’s seemingly realist stance towards man is that he is an animal that is governed by pleasure principle and mediated by the reality principle. The human animal becomes an (infinite) subject only through fidelity to Truth-proceedurs known as Events (which are unschematized openings, unlike Heideggerian Ereignis). Zizek chastises Badiou for not recognizing the way the subject retroactively constitutes his nature and thus has no natural nature, as Badiou insists, to be elevated from. For Zizek, the subject is already distorted by ‘death drive’ and thus it is only materialism that can explain consciousness, rather than as Badiou’s work suggests, the natural state of man can be understood through evolutionary-positivist type of materialism yet subjectivity proper can only be understood through his brand of materialism.

Zizek ends his piece with as statement of ‘infinite’ negation: “I believe in un-God”, as the pure form of belief deprived of its substantialization. It is clear from this why Zizek is known as a materialist theologian, as by following Badiou’s mathematical ontology, and theory of the subject, the quest for universality comes into view through the dialectizing of the logic of atheism and theism. Both Zizek and Badiou see the figure of St Paul as a model here (he universalized the teaching of Christ without placing them into prescriptive dogma): as it is through the Universality attempted by Christianity that becomes the model by which capital, which cannot fulfil the position of ‘a signifier that matters’ (Master-signifier), can be deposed.

There is a lot more from this chapter I would like to write about, but I will go into some more detail, primarily concerning Zizek’s reading of Eckhart, only after I have read through Milbank’s contribution.